Here at On a Back of an Envelope we like to honour individuals both real and fictional who have added to our understanding of Project Management or have offered an insight into the way the project world works.

Carl von Clausewitz, 1780-1831

Carl von Clausewitz was a Prussian general and military theorist whose writings on the political and psychological aspects of waging war have influenced politicians and military leaders for almost two centuries. The most famous quote from his seminal work, About War, is that “War is merely the continuation of politics by other means”. He also introduced the term ‘fog of war’ to describe the uncertainty in situational awareness experienced by participants in military operations. We can all relate to these unsettling feelings when placed in stressful situations even if not under fire.

Like many military leaders he was acutely aware of the need for planning but recognised that “The enemy of a good plan is the dream of a perfect plan.” In many respects, military operations are like projects, in that they are often unique combinations of men and materiel created to achieve a particular objective and disbanded when it is either completed or abandoned.

We can learn from his views on starting a war.

No one starts a war – or rather, no one in his sense ought to do so – without first being clear in his mind what he intends to achieve by the war and how he intends to conduct it.

Projects can be thought of in exactly the same way. The need for absolute clarity on the purpose of a project is paramount and this should be enshrined in a project vision or Vision Scope statement. During difficult moments in a project, it is worth stepping back and asking the question, ‘What is that we are attempting to achieve and how is the current situation or decision that needs to be taken going to help us achieve this?’ One practical way to determine whether a capability or item is needed is to refer to a set of requirements which have been prioritized according to a MoSCoW analysis (“Must have”, “Should have”, “Could have”, and “Won’t have”). This should enable you to decide on what is essential and what is merely a ‘Nice to have’.

von Clausewitz’s second point about being clear how you intend to conduct a war works for projects as well. Many a project has failed for lack of foresight and the temptation to resort to JFDI methodology or ‘we’ve done this sort of thing before so we will use the last project plan as a template’.

Rudyard Kipling, 1865-1936

Born in Bombay, India, Rudyard Kipling was an English journalist, poet and short-story writer. In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, as the first English-language writer to receive the prize, and at 41, its youngest recipient to date. His reputation has suffered in recent years as many of his views on the British Empire and its subjects do not always chime with current political and social views. When he died he was honoured by having his ashes interred in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey alongside other greats such as William Shakespeare, the Bronte sisters, Jane Austin and Charles Dickens.

However, his works of fiction which include The Jungle Book, The Second Jungle Book, and Just So Stories have an enduring charm and are considered classics. His poems have also stood the test of time, with If- being arguably the most famous. In Just So Stories, The Elephant’s Child describes how the elephant got its trunk and ends with this poem:

I keep six honest serving-men:

(They taught me all I knew)

Their names are What and Where and When

And How and Why and Who.

I send them over land and sea,

I send them east and west;

But after they have worked for me,

I give them all a rest.

I let them rest from nine till five.

For I am busy then,

As well as breakfast, lunch, and tea,

For they are hungry men:

But different folk have different views:

I know a person small—

She keeps ten million serving-men,

Who get no rest at all!

She sends ’em abroad on her own affairs,

From the second she opens her eyes—

One million Hows, two million Wheres,

And seven million Whys!

Kipling could have had project managers in mind as What, Where, When, How, Why and Who are the key ingredients of a generic project initiation document or project charter. The only significant omission is How Much but then us English do find discussions about money to be distinctly bad form. You can of course add many other items to these startup documents – business case, risks and issues, governance etc – but there is a lot to be said for keeping these simple questions in mind when starting a project. There is a tendency for Prince2 Project Initiation Documents (PID) or PMI Project Charters to balloon to epic proportions with information that really should be in a project repository.

A good technique is to practice getting the startup document on a single sheet of paper to produce a POAP – Project On A Page. Not only does it concentrate the mind on the important aspects of your project it is a document that business managers and other interested stakeholders can be given which stands a fair chance of being read and understood. Add in the top few significant risks and issues and project status (RAG status) and you have a ready-made Highlight Report that can be circulated to all those who are interested.

When your startup document is complete you should, like Kipling, be able to answer these six honest serving men.

James of St. George, 1230-1308

Employed by Edward I in the late 13th century as Master of the Kings Works in Wales, James of St. George was the architect and master builder of ten monumental castles in Wales. A 21st century visitor visiting these castles today cannot fail to be impressed by the epic scale of the walls and towers and one can only imagine the effect that these buildings would have had on medieval minds.

James’s skills were not only in the design and build of these castles but in organising men and materiel in an environment where transportation was primitive and the locals were distinctly hostile. His final project was the building of the castle at Beaumaris on the island of Anglesey in Wales. It was designed on his principle of ‘walls within walls’ and unlike some of his other castles did not have any constraints of geography or existing cities to spoil what was envisioned as a perfect fortress.

However, almost from the beginning work on the castle was troubled with financial difficulties and when Edward 1 went to war in Scotland, work all but stopped. £15,000 had been spent on Beaumaris when money ran out in 1298 and James wrote to Edward’s treasurers pleading for additional money. In what must be one of the first ever written examples of an Exception Report, James sent a letter to Edward’s treasurers explaining how the money had been used and why further expenditure was necessary.

“…we write to inform you that the work we are doing is very costly and we need a great deal of money. You should know… that we have kept on masons, stone cutters, quarrymen, and minor workmen all through the winter, and are still employing them, for making mortar and breaking up stone for lime; we have had costs bringing this stone to the site and bringing timber for erecting the buildings in which we are all now living instead of the castle; we also have 1000 carpenters, smiths, plasterers and navvies, quite apart from a mounted garrison of 10 men… , 20 crossbowmen… , and 100 infantry….”

He continued to explain to his paymasters the ongoing project burn which made his request for additional funds so urgent.

“In case you should wonder where so much money could go in a week, we would have you know that we have needed – and shall continue to need – 400 masons, both cutters and layers, together with 2000 minor workmen, 100 carts, 60 wagons and 30 boats bringing stone and sea coal; 200 quarrymen; 30 smiths; and carpenters for putting in the joists and floorboards and other necessary jobs. All this takes no account of the garrison mentioned above, nor of the purchase of material, of which there will have to be a great quantity… The men’s pay has been and still is very much in arrears, and we are having the greatest difficulty in keeping them because they simply have nothing to live on.”

And in a postscript which will resonate with project managers even after 800 years…

And, Sirs, for God’s sake be quick with the money for the works, as much as ever our lord the king wills; otherwise everything done up till now will have been to no avail.

Substitute ‘our lord the king’ with Project Sponsor or Senior Responsible Officer and this could be the heartfelt plea added to every request for additional project funds remembering to credit James of St. George 1298.

James received his funding but financial troubles dogged construction and although work continued for almost 35 years the castle was never finished.

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, 1892-1973

Sir Robert Watson-Watt was a British scientist and a pioneer of radar technology in the lead up to the Second World War. Often mistakenly referred to as the inventor of radar he took what was an embryo technology to create a practical system to detect aircraft. This became the Chain Home network of radar stations which ran along the length of Britain’s east coast and was an important part of the country’s air defence contributing to the RAF’s 1940 victory in the Battle of Britain.

A notable aspect of his character was his pragmatism – he was a realist and he rejoiced in what he termed ‘the cult of the imperfect’. His view when delivering to his government and military masters was:

Give them the third best to go on with; the second best comes too late; the best never comes

These days we might use the more succinct aphorism, ‘Perfect is the enemy of good’.

The adoption of Agile development within project management is often thought of as a modern invention following the publishing of the Agile Manifesto in 2001 but Watson-Watt’s approach shows us that he fully understood Agile principles even if he wouldn’t have labelled them as such.

He and his team would create a prototype to produce what we would describe as a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) – a version of the product with just enough features to be usable by early customers who can then provide feedback for future development. An MVP will create a product with minimal resources quickly to gain early feedback reducing wasted effort, accelerate learning and gain customer/user engagement. The first successful demonstration of aircraft detection by radio waves bouncing off them was on the 26th February 1935 by Watson-Watt and Arnold Wilkins in a remote field in rural Northamptonshire using a very ‘Heath Robinson’ setup and where there is now a memorial plaque.

At the end of the war, Professor E.V. Appleton made a submission to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors and said of Watson-Watt’s contribution to the development of radar, ‘…the biggest effort of all was being made by Watson-Watt in pleading, advocating, getting stores, masts and buildings. It was above all due to his drive and powerful advocacy that we had radar stations around our coast when war broke out… He had the vision of what it all implied, he just burned with it. [He] deserves a very substantial reward for his work in turning scientific radar into practical radar…

Today, we would recognise these qualities in every successful project manager.

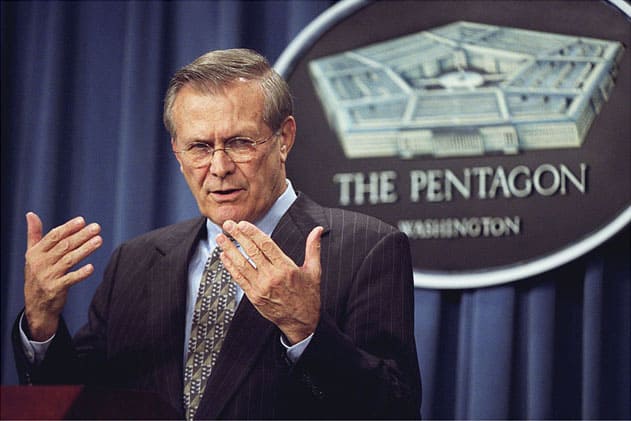

Donald Rumsfeld, 1932-2021

Donald Rumsfeld was an American politician and businessman who served as Secretary of Defense in the Gerald Ford and George W. Bush administrations. Although not the originator of the concepts – known knowns, known unknowns and unknown unknowns – he brought this to popular attention.

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.

The ideas are based on the Johari window. The Johari Window model is a simple and useful tool for illustrating and improving self-awareness, and mutual understanding between individuals within a group. The model is based on a 2 x 2 matrix that compares self and others versus known and unknown knowledge. Created by psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955. Luft and Ingham called their Johari Window model ‘Johari’ after combining their first names, Joe and Harry.

For us as project managers, known unknowns refers to risks that we can identify and need to track, and unknown unknowns are those risks which are unforeseeable and which have a habit of blind-siding even the most experienced of us.

Despite being the butt of much humour over the years, Rumsfeld named his autobiography Known and Unknown: A Memoir and in 2013 Errol Morris produced a biographical documentary about Rumsfeld entitled The Unknown Known.